Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia was the world’s largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years until the completion of Seville Cathedral in 1520. It was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1985.

Dating back to A.D. 532, the cathedral originally served as a Greek Orthodox Christian church and the seat of the Patriarch of Constantinople. When Constantinople was invaded by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, it was converted into an imperial mosque. In 1935, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, President Ataturk, changed it into a secular museum, but, in 2020, President Erdogan converted Hagia Sophia back into a mosque again.

Hagia Sophia combined two main architectural traditions from early Christianity: the Christian basilica and tomb. The first inspiration was the longitudinally oriented basilica floor plan.14 Old St. Peter’s basilica is the best example of this design. Old St. Peter’s had a long nave with a colonnade on both sides separating aisles. The nave led to the apse, the most sacred part of the basilica. There are two transepts on each side of the apse (Fig. 4).

The second building to strongly influence Hagia Sophia wasn’t a basilica but a tomb. A good example of early Christian tombs is Santa Costanza, which has a circular floor plan (Fig.5). The Christians adopted the circular tomb design from the Romans Imperial Tombs. The Romans buried their Emperors and royalty in these tombs, but the Christians reserved them for martyrs and saints.

The circular architecture really resonated with the Christian’s beliefs of the after life, because the circle symbolizes perfection and eternity. These tombs had domes that represented the dome of heaven over earth. The tomb’s heavenly dome inspired the Byzantines to put a dome on Hagia Sophia. Although Hagia Sophia has many similarities to early Christian basilicas and tomb designs, there are some key differences. First, St. Sophia’s interior has a lot more open space than a basilica. Saint Sophia has no transepts, but has an apse on the west end. Plus, the pendentives connect to two half domes on each end, while the sides are covered by walls. These walls on the sides of the pendentives have windows in them. The architects added two half domes on each end to cover the rectangular floor plan of the “nave.” The semi-domes give added support to the structure. There are multiple semi-domes added to the structure, for example the apse in under a semi-dome, which can be seen from both the interior and exterior (Fig. 6).15

Also, the interior has an added gallery above the nave. Galleries are not present in early Christian basilicas, but are found later in Romanesque designs.The open interior space and massive dome of Hagia Sophia resembles the Pantheon more than a basilica, but there are two big differences. First, the Pantheon’s dome rests on a cylinder with a circular base (Fig. 7). In comparison, Hagia Sophia’s dome rests on a square base and rests on pendentives, as stated earlier. Second, the Pantheon was made out of concrete. By this time the Byzantines had lost the knowledge of using concrete. This didn’t stop the Byzantines; they just built their masterpiece with ashlar masonry and brick.16 While the interior’s columns are made with beautiful polychrome marble.17

Many basilicas have very narrow space in the nave, but Hagia Sophia’s interior has a lot of open space.

Mosaics and frescos have played an interesting role in Hagia Sophia’s history. Mosaics graced the walls of Hagia Sophia after its construction in 537 AD. All of the original Mosaics were destroyed in a period of iconoclasm, under the rule of Leo III in the late 720s.18 Leo III felt that images were idol and so he banned all frescos and mosaics. The mosaics were restored a couple decades later. The Empress Irene loved icons so she restored the artwork. The argument against iconoclasm is that the artwork is important because it has symbols that teach stories and convey messages. Today there are still fragments of mosaics left over from after the iconoclasm periods. One of the most beautiful mosaics is of Mary and the Christ child found in the apse, above the altar (Fig. 8). There are also frescos of cherubim angels found in the pendentives (Fig. 9). There are mosaics of Christ and the apostles throughout the building. All of the mosaics and frescos were covered in plaster when the Ottomans invaded Constantinople and converted Hagia Sophia into a mosque.19

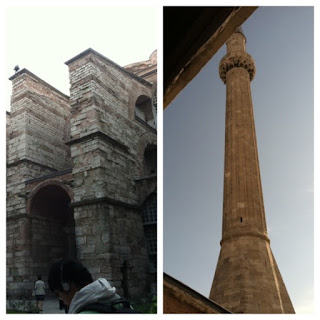

Today, Hagia Sophia is a museum, but it shows both Islamic and Christian characteristics. There are believed to be more frescos covered up by the Islamic art and gold leaf. The people of Turkey are hesitant to remove any more of the Islamic art, because they like how Hagia Sophia showcases both Islamic and Christian art.20As mentioned earlier the Ottomans invaded Constantinople and converted Hagia Sophia into a mosque in 1453 AD. The Muslims covered the mosaics and frescos with plaster, which actually preserved them. The Ottomans honestly saved Hagia Sophia, by added flying buttresses to the building. The flying buttresses removed the pressure the domes and semi-domes put on the exterior walls and redirected it to the foundation. This helped prevent the structure from eventually buckling on itself. Today, the flying buttresses can be seen from the exterior of the building (Fig. 10). The Ottomans added four minarets to Haiga Sophia; these are the towers at each corner of the structure (Fig. 10 & 11). Mimar Sinan was the architect responsible for all of these additions to Hagia Sophia. Ultimately, the Ottaman Turks may have changed many things in Hagia Sophia, but they are also responsible for saving and preserving the building’s history.21

Ultimately, Hagia Sophia is the combination of many ideas and cultures. From its early Christian roots to its Islamic influences, it is truly one of a kind. Its uniqueness has inspired many spinoffs in both the western and eastern parts of the world. The innovative use of pendentives was the first of its kind. Justinian’s obsession to build Hagia Sophia put a massive strain on his people. His aspirations to build a magnificent structure made him overlook practical design. The building suffered from engineering flaws for hundreds of years. The dome fell during an earthquake and was rebuilt with added support. The Byzantines built Hagia Sophia, but it was the Ottomans who truly saved it. The Ottoman Turks added flying buttresses to support and preserve the building. The Turks made many changes to the building when they turned it into a mosque. They covered up the Byzantine mosaics and frescos, but ironically preserved them. Many cultures have influenced the beautiful Hagia Sophia, its history, architecture, and design, so it can truly be considered the crossroads of ancient civilization. Search for: